DIRECTED BY: F. Richard Jones

STARRING: Ronald Colman, Claud Allister, Joan Bennett

NOMINATED FOR: Best Actor in a Leading Role (Ronald Colman)

Best Art Direction (William Cameron Menzies)

The transition from silent films to sound was perhaps most dangerous for the actors. If an actor didn't have a voice to match the physical persona they had built up in their silent career, they might never find work again. The most famous case of this was the career of John Gilbert, though his unexpected (but not bad) voice really only played a small part in his steep decline.

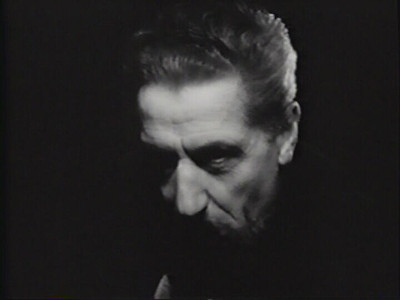

British actor Ronald Colman was one of the few stars that not survived the transition, but flourished in it. He had a great voice, and thanks to a side career in radio, knew how to use it. He had a natural charisma that he put in most of his roles, and found success in all kinds of films, be they action, comedy or romance, of which Bulldog Drummond is all three.

The character Bulldog Drummond was created by British author Herman Cyril McNeile as sort of an answer to the rise of American pulp novels. Unfortunately, like a lot of British writing in the early 20th century, McNeile's stories contained a lot of racism and general thugishness that would make the character an unacceptable hero today.

Fortunately, both Ronald Colman's and Bulldog Drummond's first foray into sound exorcised these negative elements, and what you're left with is a cool actor playing a character who's just simply BETTER then everybody else.

Throughout the film, the character of Bulldog Drummond, a retired World War I captain living in the British high life, goes around with a smirk on his face. He knows he's so much better then the people around him, and he's loving it. We're introduced to him reading in a gentleman's club full of old farts. A servant accidentally drops a spoon, upsetting the silence, and the old farts get cranky, and all Bulldog Drummond can do is laugh at how stuck up these people are. Then he starts whistling.

Because he's just simply BETTER then them.

The character of Bulldog Drummond is a bit unique, because he's not a professional crime solver, just a guy who's bored and looking for adventure. He's not even looking to help people, as his classified ad suggests.

And he does find adventure in the form of a girl's kidnapped uncle, but even on the case, he never starts taking anything seriously, even around the girl who hired him.

And most people would take this situation VERY seriously, because once Bulldog agrees to try and free the girl's uncle, he finds himself transplanted into a rather dark and very dangerous pulp world.

In a world with mad scientists, murderers in the shadows and secret passages, you'd expect a hero to stay focused and serious, but Bulldog Drummond is just so much BETTER then everybody.

And that's ultimately where the film's entertain value comes from, Bulldog Drummond smirking and easily outwitting all these dangerous criminals who want to cause him serious harm. I didn't smile during the action scenes, I smiled at small moments like Drummond playing a little tune on his car horn to mock the crooks he just escaped from.

In many ways, Bulldog Drummond is the grandfather to the wisecracking antiheroes who throw around one-liners with each victory, guys like Bruce Willis' character in Die Hard, but perhaps Drummond's nearest relative is this guy:

That's what Drummond is. A cartoon. Just like Bugs Bunny sticking his fingers into Elmer Fudd's gun barrel and having it backfire, the rules just don't apply to Drummond, and he always ends up on top. Part of that comes from the script, but a lot of the credit needs to go to Ronald Colman, who's light smirk and general body language really sells the character's superiority over everyone else.

Perhaps it's because it's such a rarity for a hero to go through no hardships at all that makes the film as enjoyable as it is, a contrast to the struggle of the heroes of every other film. I'm sure it'd get boring really fast if more good guys had it this easy. Bulldog Drummond would probably trump any of those guys, though. Bulldog Drummond is just BETTER then everyone else.