THE CROWD (1928)

DIRECTED BY: King VidorSTARRING: James Murray,

Eleanor Boardman,

Bert RoachNOMINATED FOR: Best Picture, Unique and Artistic Production

Best Director, Dramatic Picture (King Vidor)

An intersting question is posed in Preston Sturges's 1941 film

Sullivan's Travels: What film better serves the people, the tragedy or the comedy? Realism or escapism? Do people want to see their world reflected back at them, or see a fantasy with a happy ending?

Why not both? Why not laugh at our tragic world?

Maybe I'm a sick, twisted person, but I laughed more at King Vidor's

The Crowd then I cried.

The Crowd is not a comedy, it's 100% tragic drama. People lose their jobs, children die, parents die, and by the end all seems hopeless. AND I COULDN'T STOP LAUGHING.

This might just be because I see so much of my own personal history in the film. The actual events of the film aren't even close to what have happened to me and my family, but the same feelings of half-assed enthusiasm, of "waiting for my ship to come in" ring true of many different moments in life. Maybe I'm just laughing at myself.

The film opens on the 4th of July, 1900. While everyone else is celebrating, Mr. Sims impatiently waits for the birth of his son, John Sims, who comes out of the womb rather clean. Mr. Sims glows, and promises to give his son every opportunity.

Twelve years pass. John Sims is now a young boy, and he and his friends sit on a fence and discuss what they want to be when they grow up. I've seen this film three times, and on the third time I think I figured what King Vidor was doing here. The boys on the fence are acting as a scale of sorts, measuring the childrens' future plans from the most expected of them to the most absurd.

On the far left, we see the group's one black friend, who aims to become a preacher, submitting to his own racial stereotype.

On the far right, a wimpy nerd child wishes to become a cowboy, which is of course impossible, because a) a cowboy isn't an actual occupation, and b) this kid's got Wet Willie written all over him.

And smack dab in the middle is John Sims, who doesn't have a clue what he wants to be, but echoing the words of his father, he thinks he's going to be something big.

However, the scene is cut short when a horse-drawn ambulance pulls up to John's house. It turns out that John's father died for an undisclosed reason, leaving John alone to face the world.

This moment of John having his support system ripped away from him is symbolized by an amazing shot of John slowly walking up the stairs to his father's body. King Vidor takes a riff from German expressionism, shooting the stairs so it looks like the walls are expanding outward, giving the illusion of space expanding as one goes up the stairs. The crowd of friends and loved ones remain below while John walks into this big new world, all alone with no one to guide him.

Now, for many films, a parent dying might just be used as a throw-away tragedy, but once again, on my third viewing, I realized just how important this moment is to the rest of the film. John's father wasn't rich. but based on the size of their house, Mr. Sims was pretty well off and knew how to make it in the world. With this life compass taken away from him, John Sims can't grow up anymore.

So, when we see John at the age of 21 on a boat to New York City, we find he's basically a giant man-child. Wearing big man clothes and a goofy smile, carrying a suitcase with his name on it in big bold letters, and dreaming of his future with the same unspecified optimism he had at the age of 12, it's clear that without his father's guidance, John hasn't grown up much these past nine years.

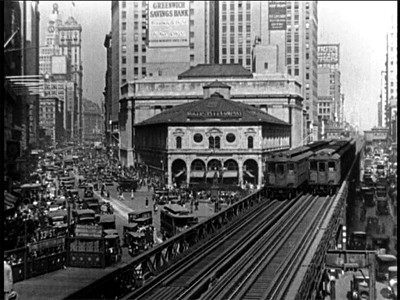

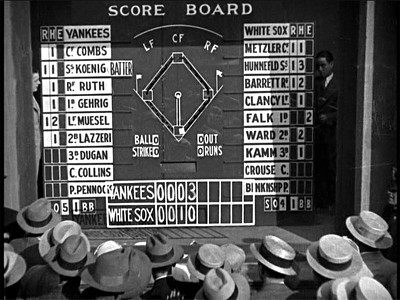

John's arrival to New York City triggers the film's most famous moment: a montage of city scenes, which Vidor filmed candidly. The montage is in three parts. The first part scenes of crowds racing around, a sea of people for John to get lost in:

In one scene, a window reflects a crowd on top of another, the crowd losing itself in itself.

The second part of the montage gives us a bird eye view of different parts of the city, showing us just how big the city really is:

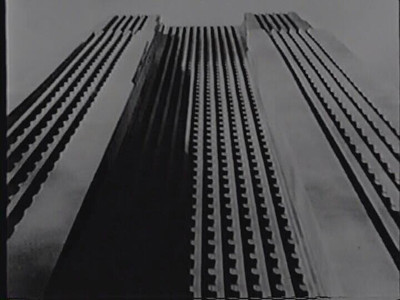

The final part of the montage shows us skyscrapers from the ground, giving us the same view as the crowd, showing off just how big the buildings are. In effect, the entire montage has given us three means to measure the size of this city (the population and both the horizontal and vertical scope of the city) and how small one person is in comparison.

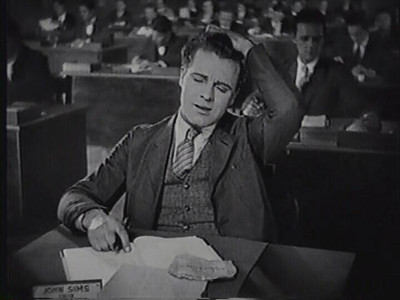

The montage ends with a shot of a model building. In a wonderful bit of early special effects, we pan up the building and zoom into one window, slowly enter the building to find a sea of workers at their desks, and slowly zoom in to one desk to find John Sims now hard to work as one of the crowd.

The film makes the point that very few people stick out in the crowd. In a scene where John uses the washroom, he encounters three people who repeat the same bad joke, and John comments on how they all talk alike. The washroom itself reflects this conformaty literally, as two walls of mirrors multiple the same people to infinite.

In fact, when we're introduced to John's friend Bert, the film has to go so far as breaking the fourth wall by having Bert look directly into the camera, as a way of saying, "Hey audience, you should pay attention to this character."

Bert drags John into a blind-double-date, where he gets paired with plain-Jane office girl Mary.

This scene really shows how dated the film is. John and Mary's date shows a lot of pre-feminism behavior, with John teasing Mary's womanhood, touching her without asking, and being generally invasive. If a guy acted like that on a first date these days, he'd get cuffed faster then the Roadrunner. Oh well, you can't change history.

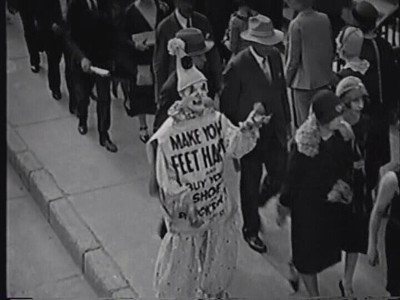

While riding on top of a double-decker bus, John and Mary spot a clown advertising a shoe store. While this is the build up for a payoff much later in the film, this scene works on it's own by showing us the extreme a person has to go to get noticed in the crowd.

So, after a long night at the local fair, John and Mary take the bus home, with Mary snoozing on John's shoulder. John sees a housing advertisment on the wall, which inspires him to ask the drowzy Mary to marry him. She nods and then goes back to sleep.

And so they get married, and take a typical honeymoon at Niagra Falls. This theme of "life dictated by advertisment" is recurring throughout the film, sort of an early anti-commercial backdrop seen in a lot of modern-day films. We learn early in the film that one of John's hobbies is coming up with ad slogans, and whilst riding the train to their honeymoon, John and Mary plan out their lives by using newspaper ads as guides.

Reminds me of when I was a little kid. My dad used to collect architecture magazines, and I spent a lot of time constructing a dream house by picking and choosing different parts from different houses from different magazines.

Anyway, after discovering their dream home in news print, they turn the page.

Considering how caught up they both are in the fantasy, Mary's reaction is understandable.

The honeymoon ends, and after a few months, John and Mary settles down in a small apartment next to some railroad tracks (which, if we've learned anything from

Se7en, is one of the worst things in the world). These apartment scenes hold the "Leave it to Beaver" distinction of showing the first toilet on film.

The couple are at first happy, though it's clear that John is a bit of a slacker. While Mary cooks meals and calls fix-it-men and other pre-feminism house wife stuff, John sits around with a ukulele and sings about how his big break is coming, yes sir.

As sadly is the case with many couples (including my recently now-ex roommates), things get worse. Small problems with the apartment build up, and John blames Mary for every single one of them ("Why didn't you call the plumber? Why didn't you tell me this was broken?"). After a long, painful breakfest scene, Mary decides she can't take it anymore and starts packing. We later learn that she's really just acting out and waiting for John to stop her.

But he doesn't. He just yells at her and leaves. Mary is shocked. What comes next is a great moment in pantomime as Mary cries over her situation, and then realizes that she forget to tell John

a little something...

Awesome.

Mary's pregnancy puts life back into their marriage, and nine months later, Mary gives birth to a baby boy. The scene in the hospital, with John playing the pacing, fidgety father-to-be, is pretty funny, but it also includes this shot, which I again really only noticed the third time of watching it.

Compare it to the earlier scene of young John going up the stairs.

With the angle of the walls and the direction John is facing in each picture, it's almost as if they're mirror images of each other. If this were a different film, you could succesfully cut these scenes together to show a boy, losing his father, quickly growing into a man, becoming a father.

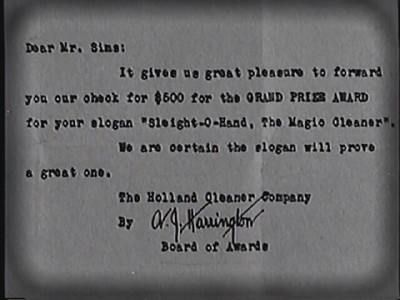

Years pass (time flies quickly in this film), and two things happen, Mary and John have a daughter, and John gets a small raise. It's clear at this point that John has no chance of moving up in the world. All John does is play his little guitar and write slogans. One day, Mary suggests John submit one of his slogans, and he finally does.

And I guess years of practice pay off, cause John earns 500 dollars. In a moment of consumer glee, John and Mary spend the whole thing on clothes and toys as opposed to anything they actually need. Mary and John gleefully tell their children, who are playing on the other side of the street, to come home.

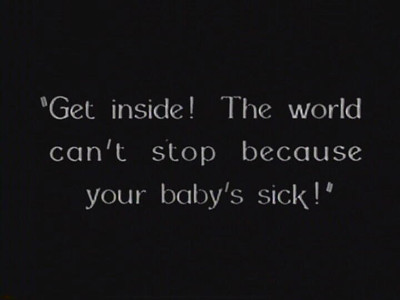

Happiness never lasts.

The pain of this scene is stretched for a while, cause John and Mary's daughter doesn't die right away. While the doctor attends to her inside the apartment, we get a sad scene of John trying to tell the world to be quiet so his child can get some rest.

Sadly, John's daughter passes away, and John enters a long depression. He becomes less active at work, and his bosses (which now include Bert) are starting to notice. In one great scene, we see John's thoughts play out on his forhead as he tries to crunch numbers.

Why don't we get neat visual moments like this anymore?

When his bosses bring up his work performance, John gets so upset that he violently quits his job, tossing around desks and papers as he goes out the door. Mary doesn't take the news too well, but being the level-headed on in the family, she encourages John to go job hunting.

And he finds a surprising large amount of jobs for that time period, including a door-to-door vacuum salesman. He just quits them all. Being without employment has made John realize just how hopeless of a case he is, so he slinks further and further into depression and uselessness.

Finally, after months of moving around, with no money, Mary can live with the man she married anymore, and packs up to leave. John, about as depressed as he could possibly be, decides to take one last walk with his son.

Assuming that there's nothing left going in his life, he throws a ball down a bridge for his son to catch. With his son distracted, John decides now is the time.

Sadly/luckily (depending on your point of view), John is too much of a coward to take his own life. When his son returns with the ball, he tells John how much he loves him. This somehow puts some spark back in John, so he runs to the city in search for a job.

However, this movie was made right before the Great Depression, and even though things hadn't fully collapsed, jobs were still hard to come by. The only thing available, in a moment of cosmic irony, is as an advertising clown.

John comes home with a pocket of change and a smile on his face. Mary is about to leave. John, with a tiny bit of confidence back, tells her he won't stop her. Oh, and can she find someone to go to the circus with her and their son? He bought three circus tickets and he wants his son to have a fun time.

Oh, how could you not love that lug?

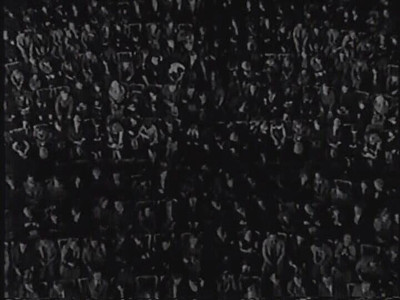

And so we come to the end of our film with a moment of temporary happiness as the entire family enjoys the circus.

What an amazing film, and rare for it's time. It's very much an early art house film. It lacks a solid plot, it stars a bunch of unknowns, and has many multi-layered themes, many of which I haven't even touched. I could really write a book on this film, each time I watch it I learn something new. Fews films do that for me.

Say good-bye, Mary and John have to leave you now. They have to get lost in the crowd.