DIRECTED BY: Frank Borzage

STARRING: Janet Gaynor, Charles Farrell, Ben Bard

WON: Best Director, Dramatic Picture (Frank Borzage)

Best Actress in a Leading Role (Janet Gaynor)

Best Writing, Adaptation (Benjamin Glazer)

NOMINATED FOR: Best Art Direction (Harry Oliver)

Best Picture, Production

I didn't like Street Angel. The first half of the film had little to do with the second half, and it's dated politics didn't help much. Lead actress Janet Gaynor was good with what she had, but she didn't have much.

So now, we go back in time, with 7th Heaven. It has most of the same cast and crew. The same director, the same two lead actors, the same studio, and a year less experience for all of them. You could say that I was dubious going into it.

HOLY CRAP 7TH HEAVEN IS THE EXACT OPPOSITE OF STREET ANGEL!

Whereas Street Angel moved too quickly through it's timeline and gave us little character development, 7th Heaven takes it's time and allows our characters to simmer. Whereas Street Angel pulls the old "love at first sight" trope, 7th Heaven allow the characters to fall for each other naturally. Whereas Street Angel's main character found love despite her disposition, 7th Heaven's main character found love by overcoming her disposition.

It's just an all-around better movie, and it's hard to believe that Street Angel is its follow up.

Our film opens in Paris, on the cusp of World War I. We're introduced to Chico, played by Charles Farrell, a city sewer cleaner who dreams of moving up the next rung in the ladder: from sewer cleaner to street cleaner.

This begins the theme of people striving to move up. In Chico's case, literally, from deep underneath to the city to it's streets, where he can be seen and his work more appreciated. Diane, played by Janet Gaynor, is also striving, but her journey is emotional, not literal.

Diane lives under the whip of her older sister, Nana, both Paris prostitutes. Diane is an honest and good girl, but she doesn't have any guts. She won't stand up for herself, and she won't take the necessary steps to pull herself out of her hellhole.

A long-lost uncle shows up, and agrees to take the two girls away with him if they've been "good." Diane can't lie, and the uncle leaves with a huff. Nana is furious, and chases her out into the street and nearly beats her to death. Fortunately, Chico happens to be working right underneath them, so he climbs out and chases Nana off.

As much of a bitch as she was, Nana was Diane's only grounding, and without her, Diane finds herself adrift emotionally. There's no goals to strive for, nothing to look forward to. These scenes of Diane sitting there, her eyes blank, her face expressionless, are juxtaposed by Chico and his coworkers eating their lunch, talking big and mighty and talking down to Diane's profession. Diane attempts suicide, but Chico prevents it.

Chico is an atheist, and loud about it. He gave God several shots to make his dreams come true, to give him the street cleaning job and to give him a blond-haired wife, and God was silent on both of them. And if he doesn't grant wishes, there's just not much point in believing him, right? (For the record, I'm an atheist, and this film makes a far better case against it then any Christian I've talked to)

This conversation catches the ear of a wandering priest, who just happens to have the power to give Chico his street cleaning job! At almost the same time, Nana returns with the police, accusing Diane of prostitution, but Chico, out of his character, steps in and claims Diane as his wife. The police says that they'll send an officer to Chico's place to confirm this. Chico finds he has no choice but to let this... woman stay at his place for the next few days.

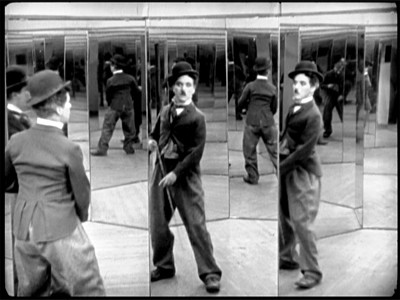

So Chico takes Diane to his apartment. As a dreamer of big things, he naturally tries to live as close to the stars are possible. In the film's most famous scene, we watch, without any cuts, Chico and Diane ascend seven flights of stairs, straight up.

Inside his apartment, up in the sky, in his element, Chico begins to transform for the audience from something of a loud mouth to just a big guy with big dreams that he wants to share with everyone. In a bit of irony, he almost begins to sound like a passionate preacher.

There's a wide wooden plank between his apartment and his next door neighbor's, with the street down below. Chico begs Diane to cross with him, showing her that if she wants to escape her trap, she needs courage. Diane would rather just sit by the large window, look at the stars and listen to Chico talk.

Janet Gaynor is just wonderful in this. Her character is allowed to naturally grow and progress, and Gaynor makes it work wonderfully. There's an immediacy about her. You always know what she's feeling and what she's thinking by just her eyes alone.

She does these cute little twitch movements to express a build up of emotion. With any other actress, this would look corny, but I don't know, Gaynor controls it just right that it works perfectly. Things get so emotional that there are times in the film where you just want to jump into the movie and hug her in happiness, like in the scene where Chico agrees to let Diane stay with him even after the cop leaves.

It really is wonderful. So, the two become a couple, and their journey towards the stars become one. Diane gains confidence and a strong will. Eventually, she can cross the plank without fear.

There's a lot more to this film, including a third act taking place on the battlefields of WWI, but I'll stop the review here. That's the task of the reviewer I guess, to decide how information to give and how much to leave for the viewer to discover for themselves. And I DO guess, I've only been trying to "writing about movies" thing for a few months now, and I still have a lot to learn. But I'll figure it out as I go along. And, maybe these reviews will lead me to the place I want to go.

After all, even us that don't believe in God look to the heavens.